BY GREGORY MADER

Guest Writer

My grandchildren will find this fact amazing; my children will roll their eyes.

When I was a kid, you could buy a regular-sized candy bar for a nickel. All the favorites, just a nickel. Snickers, Milky Way, M&M’s, Hershey’s, 3 Musketeers, Butterfinger, Baby Ruth, Reese’s, Kit-Kat, Nestle’s Crunch Bar, Milk Duds, even Almond Joy and Mounds Bars (both of which I have never liked – these have coconut). All for a nickel. A shiny silver coin that, according to a 2021 survey by MyBankTrackerTM, less than 8% of respondents would bother picking up off the ground. (Funny, the same survey indicated that over 46% would pick up a penny – something magical about pennies, I guess.)

Growing up on a farm in Minnesota, my siblings and I enjoyed the adventure of tagging along to town with Mom when she shopped for groceries. I’d stop in various stores to buy penny candies and candy bars. Milky Way and 3 Musketeers were my favorites. I also enjoyed Snickers, Hershey’s, and M&M’s, and as I grew older, I added Nut Goodies, Bun Bars and Twix to my favorites.

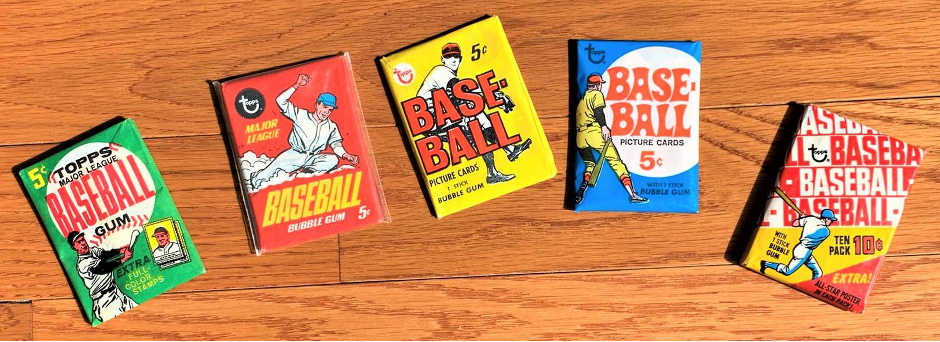

But what I saved my nickels for mostly, and purchased regularly, were baseball cards. Topps baseball cards, which came in small, colorful, rectangular packages of waxy paper, held five cards and a stick of bubble gum – all for five cents. The bubble gum was brittle, the flavor lasted only seconds, and it was inflexible, making blowing a bubble nearly impossible. But the gum was nothing. I was interested in the colorful cardboard pictures of baseball players. In the 1960s, when I was buying cards in stores, typically the local Ben Franklin, the card designs would change radically every year as would the package design.

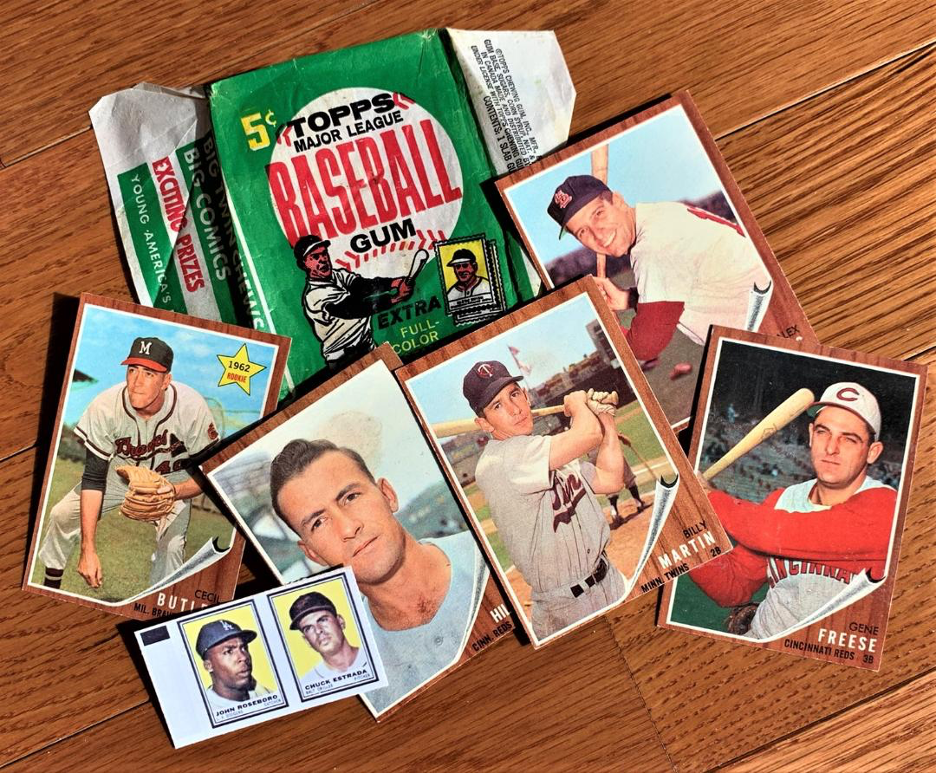

There was an anticipation to opening a new pack of baseball cards. Especially when the warmer spring days were melting the winter snow and the first packs of the new year were available. In addition to the hopefulness of unwrapping a member of the Minnesota Twins, or a star player in either league, was the anticipation of the new design the card set would employ. I would typically buy one, sometimes two packs at a time. I would slowly open the pack, not tearing the wrapper. Pulling out the cards, I would thumb through them, looking for familiar names, thrilling on the happenstance that a favorite player appeared; displaying disappointment if a card that I already owned, or a manager card was in the pack. (I always considered manager cards lame.) The picture below is a representation of what a wax pack would contain. Taking the cards home, I would pull out my shoebox of baseball cards and organize these new cards with my collection.

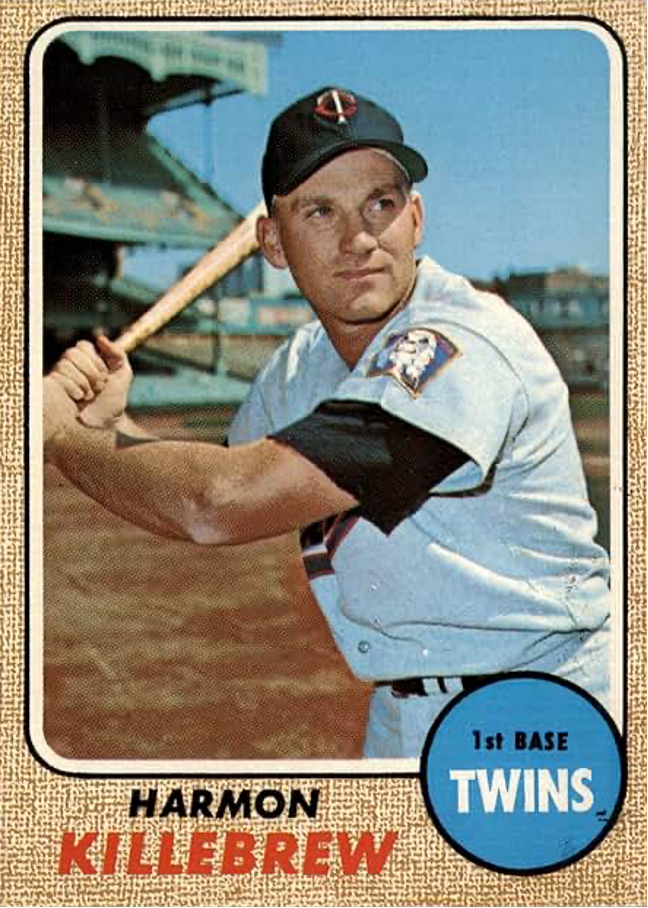

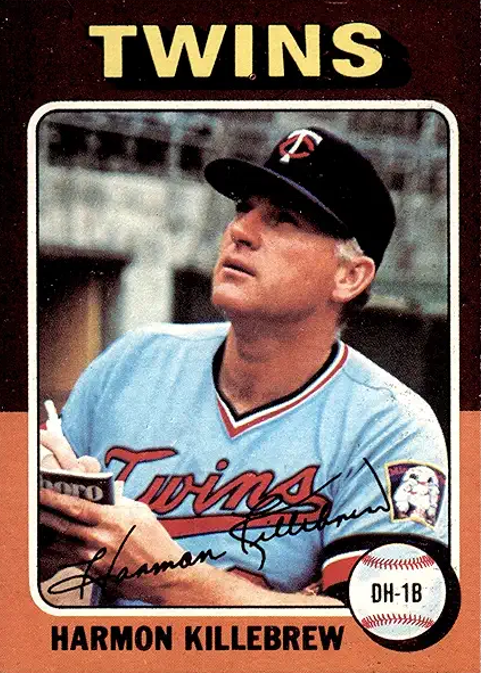

Cards also came in cello packs, which were packs of 10 cards in clear cellophane, allowing you to see the card on the front and back of the package. These sold for a dime, but didn’t come with gum, which was no loss to me. I liked seeing cello packs in a store, because I could look through the box and find a pack that had a favorite player on the top. It felt like I was cheating, but actually seeing two of the 10 cards was exhilarating. (Wax packs, with their opaque waxy cover, didn’t allow you to see any of the cards you would obtain before you opened the pack.) I especially remember a day when I found a cello pack with a 1968 Harmon Killebrew looking at me from behind the clear cellophane at a small general store in a nearby town. He was mine – and for only 10 cents!

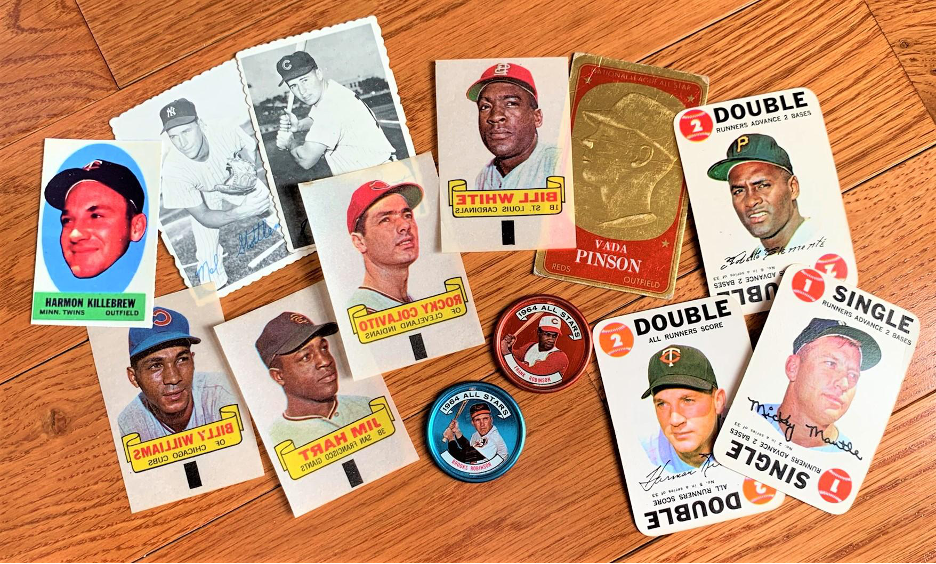

Cards also came with inserts, which comprised a subset of cards that are not part of the regular set. They had a unique design apart from the regular issue and were not necessarily produced of cardboard like the regular set. Inserts in the 1960s appeared as decals and stickers as well as coins and newsprint posters – or a smaller cardboard piece with a design radically different from the regular set.

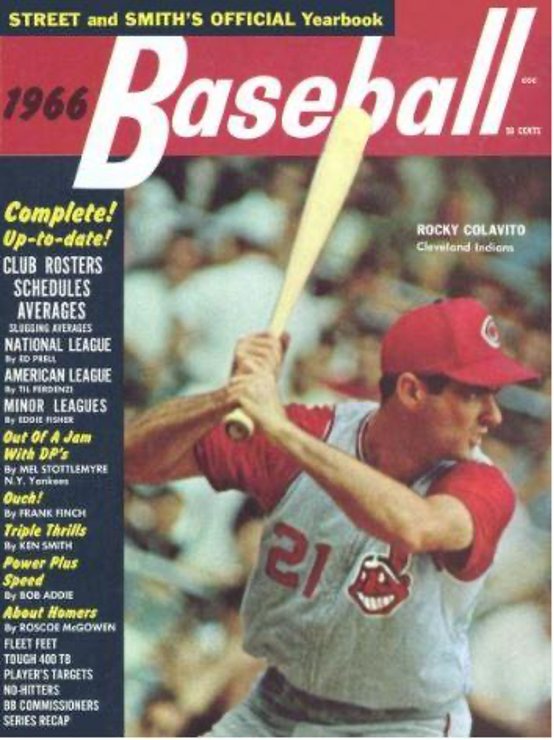

Cards were my window into what players looked like. The Sunday newspaper sports section would have tiny head shots of players (perhaps 1 1/2 inches by 3/4 of an inch), but usually just a few each week that were connected to a story about the previous day’s games and they were printed on peach-colored newsprint. Baseball cards had, for the most part, clear, color pictures, close-ups of players’ faces, or in a baseball pose, either batting or throwing. There were some baseball preview magazines that would predict the upcoming season, and these provided some pictures of players, “Street and Smith” for example. “The Sporting News” also offered pictures and lots of information each week, but that was a periodical I rarely purchased until I was much older. Baseball cards were standardized, more attractive, and more economical. I was interested in obtaining as many baseball cards as I could.

“Street and Smith’s Baseball” and “The Sporting News“

To this day when I think of players from my youth, I see them in my mind as a picture from a baseball card.

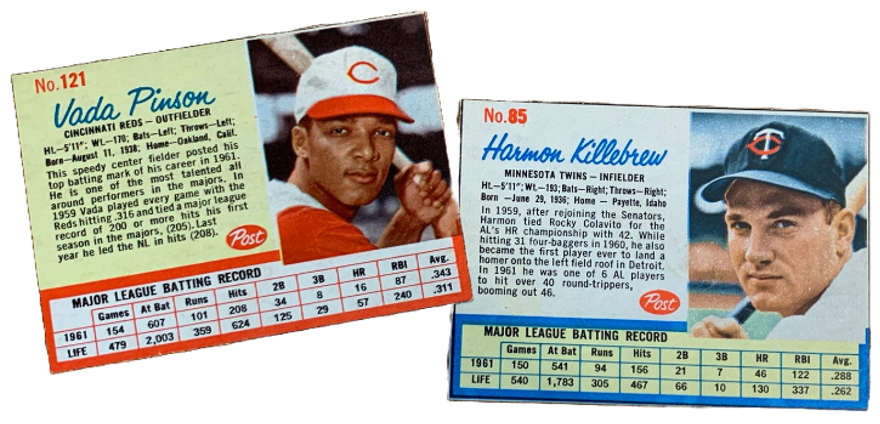

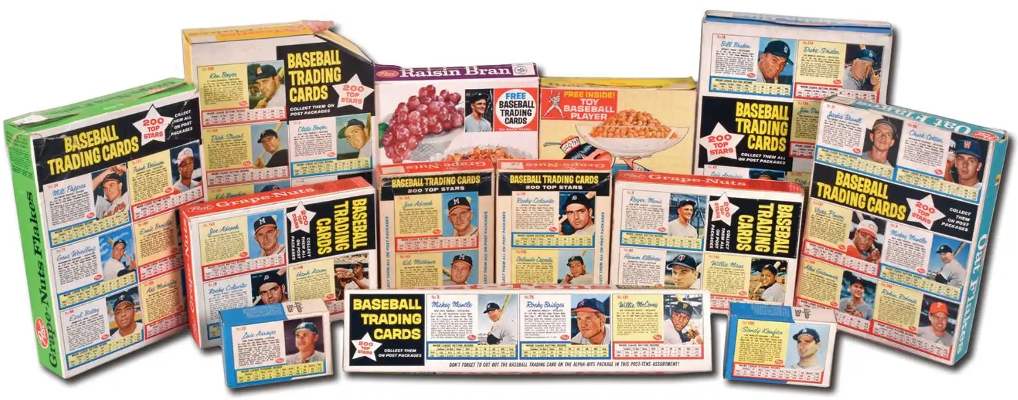

Most of the cards that my brothers and I had when I was four, when my interest in cards started, were from the backs of Post cereal boxes or on the backs of boxes of JELL-O. (I recall that our farm neighbor, Catherine, would save me JELL-O boxes that had cards on them in 1963.) From time-to-time one of my brothers would have a printed card that was sold in stores, but it was most likely acquired through a card trade at school. These were cards produced by the Topps Chewing Gum Company. Topps was basically the only game in town when it came to baseball cards. Fleer was producing smaller sets, but Topps was the only gum manufacturer that produced cards with current major league players.

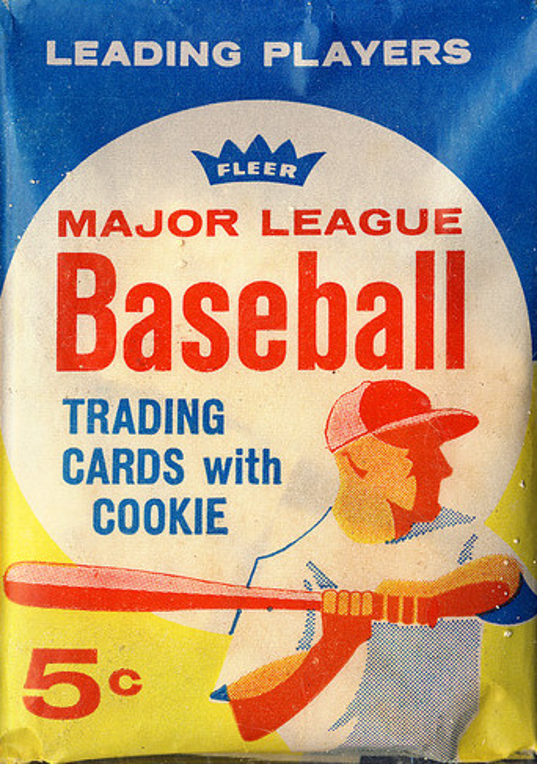

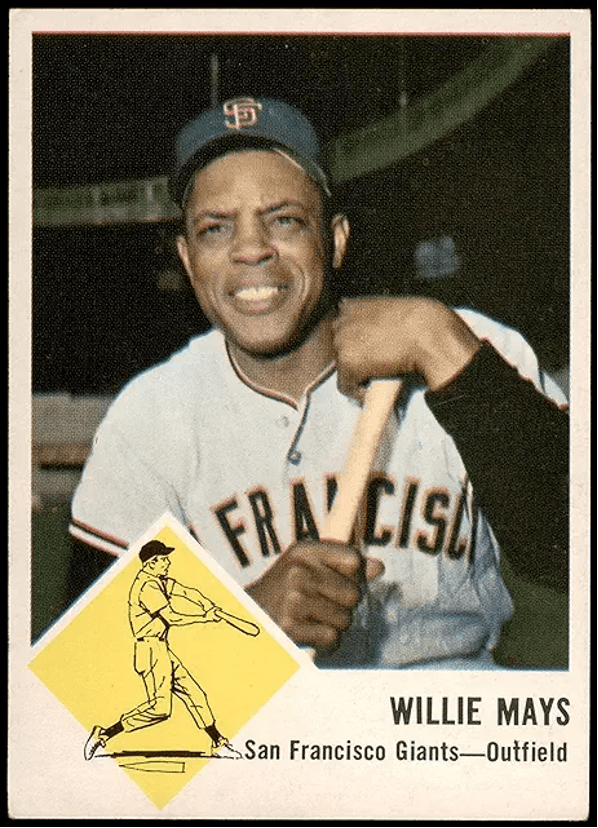

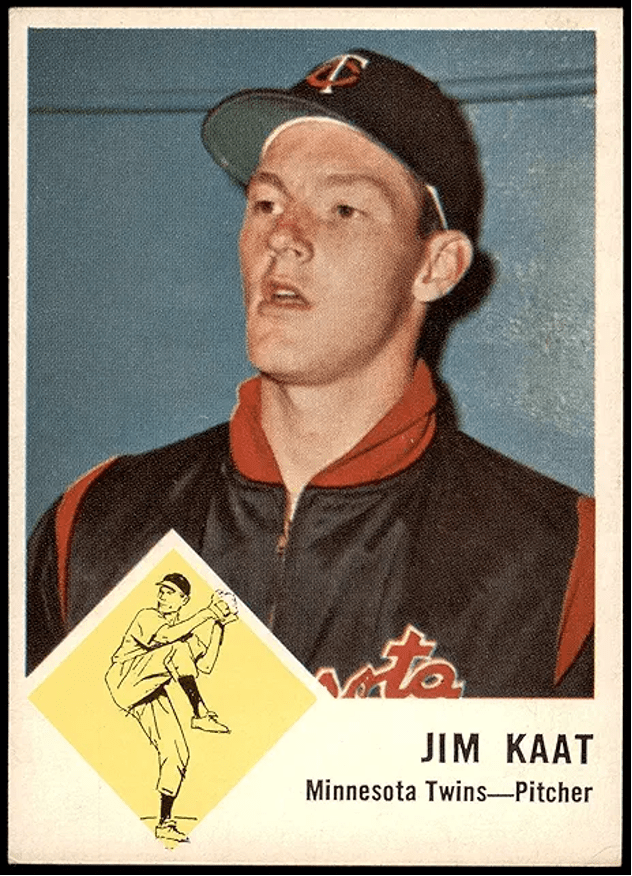

The exception to Topps’ monopoly on the production of cards featuring current major league players is the 1963 Fleer set which introduced a set of current players. Fleer’s set was packaged with a cherry-flavored cookie rather than a stick of gum. Topps and Bowman (which was purchased by Topps in 1956) had been signing baseball players to exclusivity contracts since 1950. With its purchase of Bowman, including Bowman exclusivity contracts, Topps had more than 6,500 current and former professional baseball players under their control. (Hylton, J. Gordon, “Baseball Cards and the Birth of the Right of Publicity,” Marquette Sports Law Review, Vol 12, Issue 1, Fall 2001 — Link ). Fleer filed an anti-trust complaint against Topps with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 1962, claiming Topps engaged in unfair competition through exclusivity contracts and won a preliminary hearing of the FTC. Evidently Fleer felt confident enough to decide to enter the market and printed a first series consisting of 67 cards (12 of who are Hall-of-Famers), which sold in stores alongside Topps’ regular issue in the spring of 1963. However, before a second series could be printed, Topps won an injunction against Fleer stopping the continuation of their new product. Fleer was forced to drop their plans for a 1963 set and it would become a card collecting footnote. Defeated, Fleer sold its players’ contracts to Topps in 1966.

1963 Fleer pack along with two of the 12 Hall-of-Famers in the set

Topps was also producing large sets of cards, nearly 600 in a set, but the entire set was not available all at once. Cards were sold in series. In my early years of collecting, Topps produced 88 cards in each series. The first series, released in March, consisted of a selection of these 88 cards. Each month an additional 88 cards were released through the start of September, when the final series was released. In this way, Topps kept up the interest in collecting the entire set, and selling kids lots of duplicates as they kept buying cards in order to get all the players in the series. Of course, kids would trade their duplicate cards with each other to complete the series, but the company was still selling lots of nickel packs. Topps would also make certain that star players would appear in each series, an additional enticement to keep kids buying cards the entire summer. The final series of cards were typically called short prints because not as many cards of that series were printed. This is because Topps was already gearing up to sell football cards and didn’t want unsold boxes of baseball cards coming back to their warehouse. When the card collecting hobby exploded with the return of adult collectors in the late 1970s and early 1980s, short prints started to demand higher prices because of their scarcity.

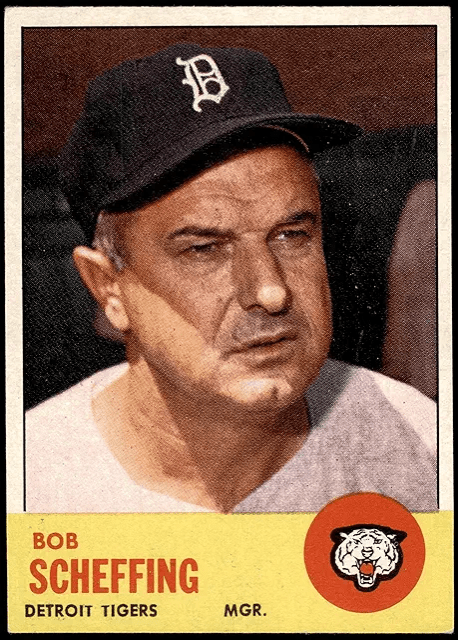

My very first Topps baseball card was a gift from Mom. She and I were running errands one day, and she left me in the car alone (amazing, right!?) to run into the bank. The car was parked in the lot between the bank and Thrifty Drug, facing the drug store. When mom returned, she had a penny pack of baseball cards that I am assuming she had purchased at the Ben Franklin store, which was adjacent to the bank. Actually, a penny pack had a stick of gum and one card. The card in my pack was the Detroit Tigers manager, Bob Scheffing, card number 134. This card would have appeared in the second series of the 1963 set, so I assume it must have been April. This was the first pack of real cards I ever had.

My first Topps baseball card

was this 1963 Bob Scheffing (#134)

When he was 11 or 12, my older brother Jim devised a game to pit the ability of players based on a comparison of their statistics. Initially the game was played using Post cereal cards from 1961 (which displayed 1960 statistics) and 1962 (which displayed 1961 statistics). He would hold two cards on top of one another to compare the stat lines, namely runs, doubles, triples, home runs, RBI, and average. Points were assigned to each of these categories. The runs, home runs, RBI, and average categories were each assigned one point, and doubles and triples, a half-point each.

Cards would be shuffled and placed in a bracketed format to face-off and find which players would advance to the next round. The “tournament” would end with the final two cards facing off against one another to declare the champion.

Since we ate a lot of Post cereals (Alpha-Bits, Sugar Crisp, Post Toasties, Raisin Bran, Grape Nuts), we had gathered a substantial number of these cards. (Funny, Rice Krinkles were in essence, Rice Krispies and Sugar Coated Corn Flakes were in essence Frosted Flakes, but I never recall the Post Cereal Krinkles or Sugar Coated Corn Flakes on our breakfast table – always Kellogg’s Rice Krispies and Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes.) Some stats on these cards were astounding. The expansion of baseball in 1961, adding two teams (the Washington Senators and the Los Angeles Angels) to the American League weakened the pitching talent, which resulted in better offensive statistics than the 1960 season. To accommodate a balanced schedule in 1961, teams in the American League played eight more games (162) than their contemporaries in the National League (154). Consequently, several players had career years. These stellar statistics added to the fun of this game.

An interesting statistical anomaly resulted. One of the players having a career year in 1961 was Detroit Tigers’ first baseman Norm Cash. He led the league with a resounding .361 average, hit 41 home runs, drove in 132 baserunners and he himself scored 119 times. His statistics were in fact, so spectacular, that he would beat every player we had that he was paired against with the exception of Rocky Colavito, his teammate on the Tigers. Colavito, in turn, could be beaten by other players. Mickey Mantle of the New York Yankees, and Jim Gentile of the Baltimore Orioles each had combinations of statistical numbers that would defeat Colavito. But, when matched with Cash, Colavito’s 45 home runs, 140 RBI, and 129 runs scored were great enough to defeat Cash.

So, Cash would end up winning the tournament about half the time. Only if he faced Colavito at some point in the contest would he lose and then another player would take the title.

An aside to this story. Turns out, we ate a lot of Post cereal, but never had a 1962 Orlando Cepeda (San Francisco Giants) or 1962 Roger Maris (New York Yankees) card. 1961 statistics on Maris’ 1962 card results in an outright win for Maris, 3-2. Cepeda’s 1961 statistical comparison with Cash results in a tie. Tie breakers were determined by comparing the triple crown statistics (home runs, RBI, and average). The tie breaker in this comparison would fall to Cepeda. Cepeda and Maris would have been the only other players to be able to defeat Cash. Examining 1960 and 1961 stat lines present day, there was no player who would have been able to defeat all players.

Cash and Cepeda’s stellar years in 1961, as shown on their ’62 Post Cereal cards

Card collecting can become a conundrum. One needs to decide to limit what they want in their collection and not stray from their collecting goals. I have strayed from time to time. I see a new product and decide that I will buy some of it to see if it truly suits my experience. Often, these are items that I discard later because they don’t bring me the joy I was seeking.

When the card hobby exploded in the early 1980s and adults entered the market, I admit it was exciting. Lots of vintage material entered the market and items that were not available became more plentiful. Several manufacturers began to produce card sets. Soon, each of these manufacturers produced many more than one set and the hobby escalated with an estimated 81 billion cards produced each year in the early 1990s (Dave Jamieson, Mint Condition New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2010, p. 7 — Link ).

I am uncertain when baseball card shows started, and even less certain when card shows started to evolve. I have read articles indicating that early shows were private swap-meets between early collectors who gathered to talk about their collections and trade cards in an effort to complete their sets and to learn about regional issues of which they were unaware. At some point they rented a small venue and invited additional large collectors who were interested in selling to and trading cards with the public at-large. (I recommend the article, “When did Card Shows Become ‘National’ Events?” by George Vrechek at OldBaseball.com. — Link .)

My early years of card shows involved a great deal of camaraderie between buyers and sellers. People in the hobby were interested in teaching; attendees were interested in learning. And there was always a lot of baseball talk. Most dealers were creating a “side-hustle” in order to expand their own collections. Everyone was having fun.

As the hobby has evolved, card collecting became less of a hobby and much more of a business. I appreciate dealers who perform the leg work to bring vintage material into a show for a weekend, but there has come a point where there is less fun in collecting because the business arena upstages the teaching/learning aspect of the hobby.

I appreciate that my thoughts are of an aging collector, but give me my due. I realize these days are gone. I just miss the opportunity of chatting up old player names and baseball history while making my purchases. I find less and less knowledge of baseball and the comradeship I had experienced at shows I attend presently. I just miss the fun.

The business of baseball cards, both new product and vintage materials have increased in price substantially in just a few years. In late 2022, I attended a card show in Bloomington (MN), my first show in three years because of COVID. I walked around the room and was astounded by the prices on cards that I had hoped to add to my collection. I spoke on the phone with my daughter, Jessie, when she called to ask how I was faring. I told her that I thought I may have purchased my last card. Don’t laugh, but it was a bit depressing. I did eventually purchase a few cards, but the hobby that I loved for so many years is not the same. Kids, who in my time, carried their cards in shoe boxes now carry combination-lock storage boxes that seem to have evolved from attaché cases one would normally see in the diamond district.

As for me, I enjoy collecting cards from the late 1950s and 1960s. I particularly enjoy the Post Cereal issues from 1961, 1962, and 1963. There are tangents in my collection, certainly, but I am not interested in expanding my collection past the days of my childhood.

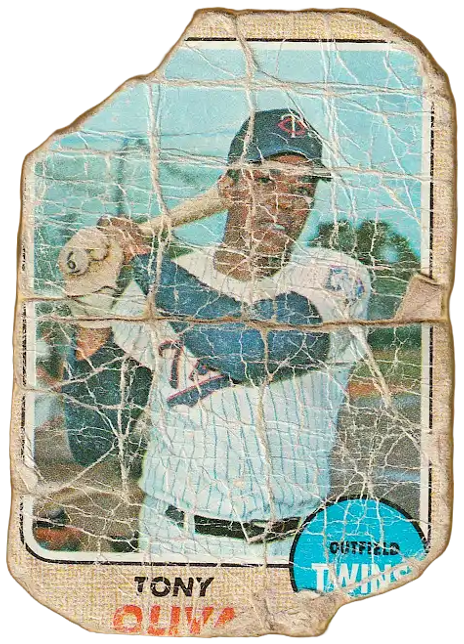

One of my favorite baseball cards was a 1968 Tony Oliva that I carried in my pocket that summer.

from my childhood

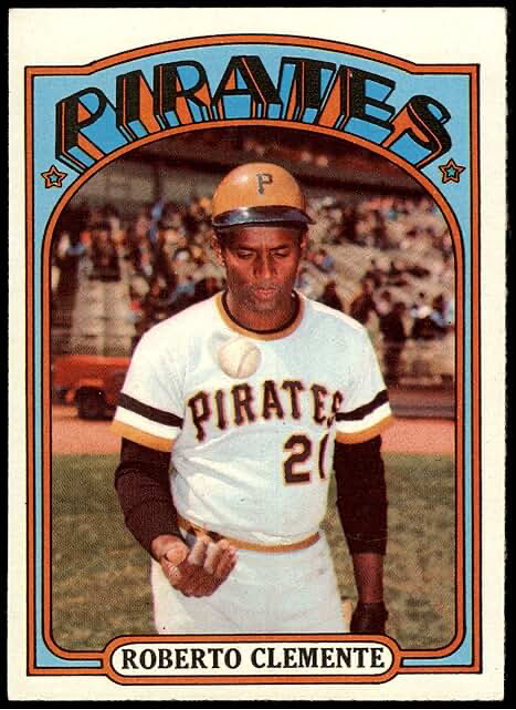

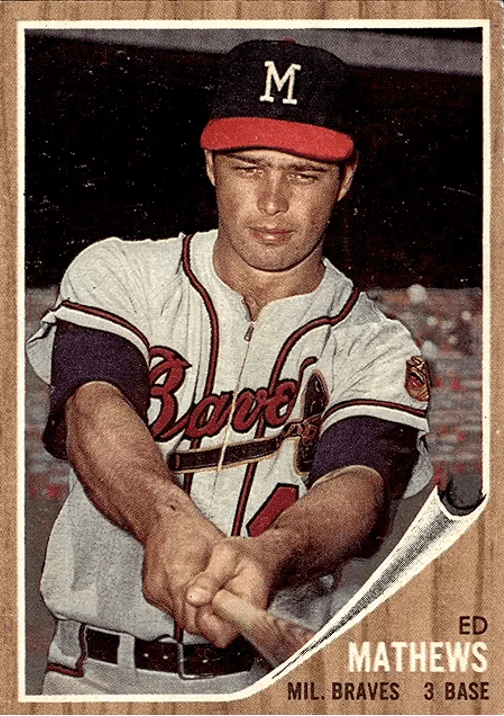

An additional note about my collection. As I collected cards, there are cards that have struck me, for the aesthetic quality of the image. I like the look of certain designs and certain photographs that are used for cards. Not entirely standard baseball poses, these cards catch a player in more of a normal everyday circumstance. It’s just that it is on the field and related to baseball. Some of these images are represented here:

Back to my collecting story. As I grew older, into my high school years, I started feeling a bit embarrassed about buying cards in a store. I was too old; baseball cards were something kids collected. Then, during my time in college, I had a chance encounter at a nearby shopping center. I noticed a few tables in one of the commons areas with men standing behind tables of baseball cards. I was intrigued. What was the story? Adults, with baseball cards? In public? I engaged in a conversation with one of the dealers and ended up purchasing a 1962 Post Cereal Roger Maris and a 1963 Post Cereal Frank Robinson. I was again captivated.

Spending my nickels? If only that were true.

some old baseball cards on a winter day.

• • • • • •

THIS ARTICLE IS AN UPDATED VERSION OF A STORY PRINTED IN BOOKS GREGORY MADER GAVE HIS CHILDREN AND GRANDCHILDREN AS A CHRISTMAS PRESENT IN 2023. IT IS REPRINTED HERE WITH PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR.

• • •

Text Copyright © 2024 by BaseballCardFun.com / Gregory Mader

No article appearing on this website may be reproduced without written consent of the Editor/Publisher

To keep up-to-date on additions to BaseballCardFun.com, subscribe below*

* Your email address will never be shared and is only used to announce new articles